Snacking on the Rise

October 14, 2024 | Article

The last decade has brought in a wealth of innovations to the snacking industry. Evolving consumption practices are dictating the industry players to develop new narratives, new food scripts, new product formats and unleash creativity through various dimensions. Consumers want to get the most out of their snacks and the brands are here to serve them.

by Richard C. Delerins & Arunima Kumar

To uncover the different consumption practices associated with snacking, it is indispensable to understand the origins of the term and the act itself. In some cultures, the term arrived as late as the 90s indicating a relatively young space for the producers and the consumers alike.

Dissecting the snacking moment in different cultures and languages thus unravels ‘food scripts’ and ‘entry points’ for snacks in the day to day lives of consumers. While snacking is an individual moment in several parts of the world where brands would benefit from individualizing their offer, it is a moment of collective respite in others where all the brand communication would centre around family, celebration or togetherness.

Snack flavours have forever been inspired by pre-existing flavour combinations often found in traditional street foods of particular countries. Today, snacks have become the international vehicle of these street foods, bringing local and niche flavours to experimental consumers worldwide. Therefore, it is vital to factor-in various rationales, themes, origin stories and driving forces governing the growth of snacking as a product category as well as a dedicated mini-meal.

The word ‘snack’ originates from 17th century Dutch ‘snacken’ (to bite). It means to have a ‘mere bite or a morsel, eat a light meal’, ‘a share, a portion, a part’ or a ‘bite or morsel to eat hastily’. The translation of the word is not straightforward in other languages and each culture defines snack in their own capacity. Some current definitions of “snack” in the literature are based on the time of day of an eating occasion, type of food consumed, amount of food consumed, location of food consumption, or a combination of several of these factors.

Culinary Cultures: the Meaning of ‘Snacking’

However, despite this ambiguity in defining the practice, in most cultures, snacks or snacking have a collective meaning which is the opposite of a meal. Although snacking is still an occasion during which people consume energy and nutrients, it has been largely associated with eating alone, short eating periods, disposable utensils etc. as opposed to a proper meal.

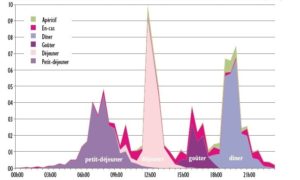

A fourth ‘meal’ or snack is part of a traditional meal pattern in several countries. In France, the word ‘snacking’ was not utilised till the late 90s early 2000s after which it steeply spiked up. The concept was non-existent and ‘goûter’ is what came closest to a snack but it was (and is still) largely sweet, for kids and taken at a defined time.

The adults have of course enjoyed the ‘apéritif’, ‘aperitivo’ and other terms for the evening ‘appetite opening beverage and finger foods’ in the Mediterranean culture for ages. The Latin ‘aperire’ from which the concept originates, literally means to open. In the context of food, to open your appetite before a meal.

In fact, the ‘apéritif effect’ – term coined by nutritionists for when consuming alcohol prior to a meal (an apéritif) – tend to increase food consumption. This greater food consumption may result from increased activity in brain regions that mediate reward and regulate feeding behaviour. This is the opposite of what a snack seeks to achieve.

The Hindi word for ‘snack’, nashta (नाश्ता), is the same as the word used for breakfast, essentially meaning something lighter than a whole meal, to break a fast or satiate hunger pangs. Much like goûter or apéritif, नाश्ता (the snack version) is taken in the evening along with a beverage, not alcohol but tea. A small meal between lunch and dinner, merienda, is customary in the Philippines. In Mexico, a midmorning meal (almuerzo) is relatively common.

The Moment and Significance of ‘Snacking’

In the American and Anglo-Saxon cultures, “salty snacks, desserts, candy, and sweetened beverages” are popular snack choices unlike traditional foods in other parts of the world. However, ‘snack’ is sometimes used interchangeably with a quick grab-&- go meal. In fact, with developments in the nutrient contents, snacks have the possibility of becoming a meal replacement as the functionality aspect takes over.

The lack of a static definition is an asset in uncovering the various food scripts associated to ‘snacking’. There are different meanings associated with the eating occasion. Snacking can stem from different motivations such as hunger, location, social environment, hedonic eating. It is even influenced by eating companions. In the American/Anglo-Saxon hustleculture, snacks are more suited for individual consumption through smaller, single serve products. Snack consumption may also be initiated because of celebratory social occasions as well as the availability of or desire for tempting food.

Especially, in cultures where meals itself are celebrated or the eating occasions are well defined, such as in France, there is not much room for snacks. The ‘moment of snacking’ is rather a collective moment, a time to get together, catch-up, chit-chat and bond with close ones. There is most likely wine or another alcohol in the mix. In eastern cultures like India, snacks are accompanied by ‘chai’ (tea) without fail. ‘Chainashta’ is a match made in heaven. This is a moment of unwinding with family/colleagues/ friends after a long day and rejuvenating before calling it a day at work.

The Geography of Snacking

Looking at the iconic, traditional snacks from around the world, it appears that processed snacks of today have been largely modelled on them.

For instance, Papadum is an Indian snack possibly from 500BC, widely popular in South Asia, made with either lentil, gram, rice, or chickpea flour baked into a thin, crispy cracker bread or sometimes fried. It can be consumed on its own, with pickles, or served with other dishes such as curries, when it’s used as a utensil for scooping the dish up. Could this have been the original inspiration for a crisp? We might never find out, but it surely sounds very similar to the multi-grain based, baked snack variations now present throughout the world.

Biltong is a traditional South African beef snack that is cured in a very unique way. Although it looks similar to American beef jerky, it is quite different in flavour and the method of preparation. The beef is dried with vinegar which cures the meat and adds layers of texture and flavour. It is seasoned with salt, pepper, and coriander, and the meat is much thicker than beef jerky. Originally, it was created out of necessity as a survival food when the Dutch settlers arrived in South Africa.

Biltong is a traditional South African beef snack that is cured in a very unique way. Although it looks similar to American beef jerky, it is quite different in flavour and the method of preparation. The beef is dried with vinegar which cures the meat and adds layers of texture and flavour. It is seasoned with salt, pepper, and coriander, and the meat is much thicker than beef jerky. Originally, it was created out of necessity as a survival food when the Dutch settlers arrived in South Africa.

The Sicilian Arancini are big, golden rice balls filled with a savoury combination of ingredients in the centre. The fillings often include meat sauce with peas, dried prosciutto, cheeses such as mozzarella and pecorino, tomatoes, or dried capers. The balls are rolled in breadcrumbs and fried in hot oil. The dish was invented in the 10th century during the Kalbid rule of Sicily. The name of the dish is derived from the Italian word for orange, arancia, referring to the similarities in visual appearance and colour, so arancini means small oranges.

The Sicilian Arancini are big, golden rice balls filled with a savoury combination of ingredients in the centre. The fillings often include meat sauce with peas, dried prosciutto, cheeses such as mozzarella and pecorino, tomatoes, or dried capers. The balls are rolled in breadcrumbs and fried in hot oil. The dish was invented in the 10th century during the Kalbid rule of Sicily. The name of the dish is derived from the Italian word for orange, arancia, referring to the similarities in visual appearance and colour, so arancini means small oranges.

Although Elote is a Spanish word for corn, it also signifies a popular Mexican street food consisting of corn on the cob that is coated with lime and mayonnaise, then rolled in crumbled cotija cheese and chili powder. It is also found in India in the form of ‘bhutta’, a celebrated street food, now an inspiration for several fusion snacks.

Although Elote is a Spanish word for corn, it also signifies a popular Mexican street food consisting of corn on the cob that is coated with lime and mayonnaise, then rolled in crumbled cotija cheese and chili powder. It is also found in India in the form of ‘bhutta’, a celebrated street food, now an inspiration for several fusion snacks.

Korean egg-bread, Gyeran-ppang (계란빵), is a popular street snack which is a sweet, steamy, hot and fluffy little loaf of bread with a whole egg inside. With the rest of the world discovering and adopting Korean delicacies at a lightning speed, could this street food be the next inspiration for snack brands?

Korean egg-bread, Gyeran-ppang (계란빵), is a popular street snack which is a sweet, steamy, hot and fluffy little loaf of bread with a whole egg inside. With the rest of the world discovering and adopting Korean delicacies at a lightning speed, could this street food be the next inspiration for snack brands?

Snacking and Street Foods: an Inevitable Fusion

Street food has been a constant source of inspiration for flavours in case of savoury snacks around the world. Even though chips or crisps were invented by mistake, the flavours were very intentionally developed. The most basic and popular ‘barbecue’ flavour (excluding the classic salted flavour), was in fact the first flavour of chips sold in the United States in the 1950s by Herr’s. In another part of the world, after some trial and error, in 1954, Joe ‘Spud’ Murphy, the owner of the Irish crisps company Tayto, and his employee Seamus Burke, produced the world’s first seasoned chips: Cheese & Onion and Salt & Vinegar, flavours that have stood the test of time.

The origin of these lies in the various street food traditions that have been passed on through generations. The rationale behind this is the ability of street food to make one feel comfortable and nostalgic. It allows one to have the taste of their favourite dish without having to go through an elaborate cooking process.

Over the years, brands have understood and leveraged this intel. Pringles introduced their street food edition in 2017 with flavours such as Thai Green Curry, Mac & Cheese etc. Frito Lay’s Cheetos followed suite with Hamburger, Pizza and Hot dog flavours in their Mix-Ups edition, offering the consumer a little bit of everything.

Hand cooked crisps brand, London Flavours launched street food inspired crisps in the summer of 2018 which included street food favourites from around the world reflecting London’s diversity such as Pho, Teriyaki, Sticky Ribs. ‘We saw an opportunity to capitalise on the high consumer demand for adventurous new street food flavours and cuisines, infusing them into a delicious range of premium crisps.’

Banana chips from the streets of Kerala, India have gotten a global makeover. Sold as plain salted for decades, they are being reinterpreted in contemporary flavours to appeal to a wider market with flavours such as peri-peri, sweet chilli, tandoori and even biryani. Beyond Snack is a brand taking the lead on this front. Snacking brands in each country highlight their local ingredients and dishes as inspiration to create snacks.

For instance, fish skin and egg are the most popular new snack bases in South-East Asian countries. But today, these local snacks are being taken and appreciated beyond their places of origin. This is a consequence of the sudden popularity of street food, partially accelerated by Pop culture (Netflix documentary, ‘Street Food Asia’) and partially by the ‘wanderlust’ spirit of the millennials who have no inhibitions in experimenting with new food and flavours from other cultures.

Looking back at iconic snacks from around the world which also happen to be beloved street foods further strengthens this interconnection. Trader Joe’s Elote Chip Dippers, Kalahari Biltong and Poppadoms, a word play on papadums, are all examples of snack foods inspired from street foods.